History of Indiana State Parks

- Natural History

- Woodland Culture

- Pioneers

- Native Americans

- Conflicts & Wars

- The Beginnings of Indiana State Parks

- New Deal

- Recreation Demonstration Areas

- Interpretation

- Baby Boom and Beyond

Other resources

2. Indiana Woodland Cultures

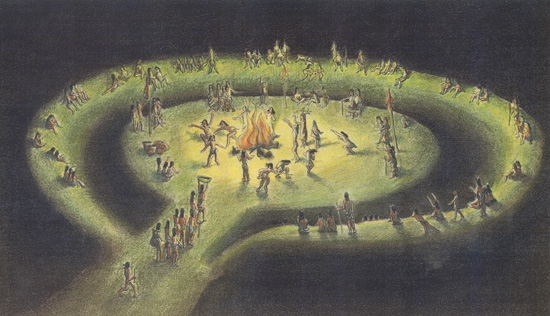

Artist's rendering of a ceremony on the Great Mound at Mounds State Park.

Adena Culture

In the Early Woodland Period, from 1,000 to 200 BCE, there was a people in Indiana we now call the Adena culture. The term is taken from the name of the farm of Thomas Worthington, who lived in Chillicothe, Ohio in the 19th century. Archaeologists named this civilization because they did not know what members of this group called themselves.

The Adena were not one large tribe, but likely a group of interconnected communities living mostly in Ohio and Indiana. The Adena were significant for their food cultivation, pottery and commerce network, which covered a vast area from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico.

Over a period of 500 years the Adena culture transformed into what we call the Hopewell tradition. Much like the Adena, the Hopewell were not one large group, but were a group of interrelated societies. And just as with the Adena, archaeologists also coined the name Hopewell.

Hopewell Tradition

The Hopewell’s large trade networks connected them with other cultures. Some archaeologists see the Hopewell as the pinnacle of the Adena. The Adena-Hopewell had a nascent social hierarchy. The evolution from hunter-gatherers to agriculture meant stability as well as economic expansion and population growth.

Out of these changes came social hierarchy, and from there tribes and chiefdoms emerged. No evidence exists of the Hopewell in Indiana after 500 CE, but some archaeologists think that sometime before European contact they became the Miami or Shawnee.

The Woodland Period is often associated with the building of mounds, also called earthworks. Many of these mounds were built by the Adena. The mounds were used by Woodland peoples for various religious and ceremonial purposes. More than 300 of these mounds have been identified in central Indiana. All of them are on the eastern side of a river.

Mound Builders

When the mounds were used by the Adena-Hopewell, they had no trees. They removed the trees with fire to keep the view open. Each mound has four main parts: embankment, ditch, platform and gateway. The embankment is the actual earthen mound, which creates the perimeter around the ditch. The dirt removed from the ditch was used to build the mound. The ditch is in the middle of the enclosure and was dug first. Dirt was loaded into baskets and placed on the mound. The platform was located in the center of the ditch, at ground level. Finally, the gateway serves as a break in the outer embankment, creating an opening for people to enter the enclosure at ground level.

The mounds at Mounds State Park were built around 250 BCE. The Great Mound is the largest among 10 found at the park. The Great Mound was most likely used for ceremonies, but we do not know for sure. The Adena built the mound but the Hopewell used it for burials. Fiddleback Mound is in the shape of a figure 8 (much like a fiddle). Archaeologists believe that Fiddleback was a midden (i.e., a trash heap), which can provide a wealth of information about a group’s daily life. The Circle Mound is actually rectangular.

Most of the mounds on the park’s map are grouped at the southern end of the property. Circle Mound is on the northern end. Fomalhaut Mound is relatively small, standing only about a foot high. Unlike the other mounds, it has two gateways. The final mound on the park’s map is Woodland Mound. It is a small mound likely used for astronomy. Archaeologists believe that the complex of mounds at Mounds State Park served to help the Adena-Hopewell track astronomical events over the course of a year.

The Mississippian Culture

The Mississippian Culture was another mound-building civilization. This people lived in the Midwest from 800 to 1,600 CE. The Mississippians built large mounds with platforms on top. On these platforms they built houses and public buildings. The staple food for this culture was maize, their name for corn. Like the Adena-Hopewell, Mississippians had a large trade network.

The Mississippians had a more fully evolved social hierarchy than the Adena-Hopewell. The hierarchy used the chiefdom as its political structure. The Mississippians left behind physical evidence of their daily life in the form of artifacts, giving us clues about their daily life. “Mississippian” is a name given to this group by modern archaeologists. It is not a name they were known by when they lived here.

The Mississippian people were agricultural, growing a lot of corn. The largest Mississippian site in Indiana is Angel Mounds near Evansville. Falls of the Ohio State Park, located along the Ohio River much the same as Angel Mounds, is known to have had Mississippian settlements.

Mississippian Settlements

These settlements typically had a central plaza with two earthen mounds. One of the mounds was specifically for ceremonial use. The other mound was used as a platform for building the chief’s house.

Around the plaza stood other buildings used for commerce and production of goods, similar to the buildings we might find in a downtown area today. Residential buildings were constructed behind these commercial buildings. Outside of the main town center were farms, villages and hamlets. Houses were made using a method called wattle and daub, which used sticks (wattles) and mud mixed with straw (daub) to build walls. These houses were covered with a thatched roof.

Agriculture was the primary source of food production for these settlements. As food storage improved, these populations were able to store food year-round and save seeds for planting the next year. And, living on a river, they supplemented their diet with fish and mussels.

At some point about 700 years ago the Mississippians suffered a terrible drought that led to widespread loss of crops. This looming starvation drastically changed the daily life of this culture. People left their towns, farms, villages and hamlets to form nomadic hunting and gathering bands.