History of Indiana State Parks

- Natural History

- Woodland Culture

- Pioneers

- Native Americans

- Conflicts & Wars

- The Beginnings of Indiana State Parks

- New Deal

- Recreation Demonstration Areas

- Interpretation

- Baby Boom and Beyond

Other resources

4. Native Americans in Indiana

Native Americans fled the territory that became Indiana during a conflict known as the Beaver Wars. These groups only returned after the wars ended in 1701. The war was fought over territory and the ability to hunt beaver for their pelts. The Iroquois were supported by the Dutch and English on one side and the tribes of the Great Lakes region, including what became Indiana, were supported by the French on the other side. Pay a visit to Potato Creek State Park and Indiana Dunes State Park to see where some of these conflicts took place and where the natives were living.

The primary inhabitants here at the time were Miami and Potawatomi. But this period also witnessed the arrival of the Lenape (or Delaware) from the east coast. The Lenape were forced westward as more Europeans began to arrive. The Lenape sought refuge in Indiana from the Chesapeake Bay after intrusion on their land by Europeans. They found a new home in what is now Central Indiana.

The Miami are in the Algonquian language family. Indiana was home to several bands of Miami, including Wea and Piankashaw. Their territory included most of the northern portion of what is now Indiana.

Indian Removal

The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi came to Indiana by way of the Michigan territory, but migrated to Indiana at some point following the Beaver Wars. Pokagon State Park is in the region of Indiana where this tribe lived. The park is named after Leopold and Simon Pokagon, two leaders of this particular band of Potawatomi.

The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi came to Indiana by way of the Michigan territory, but migrated to Indiana at some point following the Beaver Wars. Pokagon State Park is in the region of Indiana where this tribe lived. The park is named after Leopold and Simon Pokagon, two leaders of this particular band of Potawatomi.

Conflicts with Europeans eventually came to a head, resulting in the forced removal of the indigenous peoples of Indiana who had called this land home for thousands of years. Over a period of about fifteen years beginning in 1830 indigenous tribes were forcibly removed from Indiana to territories further west. Indian removal was happening on a national scale with the passage of the Indian Removal Act by the United States Congress in 1830.

The Wea and Shawnee saw the direction that things were headed and left the state voluntarily, leaving the Miami and the Potawatomi the two remaining tribes. The Wea and Shawnee experienced great hardships from pressures on hunting and land use directly related to American settlement. These groups escaped by moving west. The Potawatomi village led by Chief Menominee resisted as long as possible. He and his village were removed along what is called the Potawatomi Trail of Death in 1838.

Of the nearly 900 people removed around forty of them died along the journey. After the Trail of Death, the only natives left in the state were the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi, having gained special permission from the government to remain in the Great Lakes. In 1846, many of the Miami were removed by force. However, many stayed on land that they owned privately.

- Mississinewa Lake as the American Indians may have experienced it .

- Pokagon State Park as the American Indians may have experienced it.

Prophetstown and Tecumseh’s Confederation

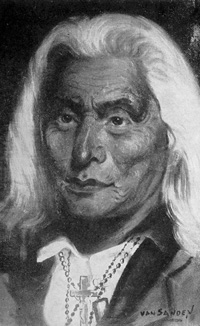

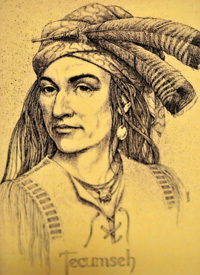

The Shawnee migrated to northeast Indiana from Ohio in the late 18th century. From there they found their way to the Vincennes area in search of better hunting opportunities. The Shawnee brothers Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa led a confederation of natives to try to win back their land and existence from the encroachment of Europeans. The brothers established an encampment called Prophetstown near present day Lafayette, Indiana. This site has become Indiana’s newest state park, Prophetstown State Park.

The Shawnee migrated to northeast Indiana from Ohio in the late 18th century. From there they found their way to the Vincennes area in search of better hunting opportunities. The Shawnee brothers Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa led a confederation of natives to try to win back their land and existence from the encroachment of Europeans. The brothers established an encampment called Prophetstown near present day Lafayette, Indiana. This site has become Indiana’s newest state park, Prophetstown State Park.

As European-American settlers moved westward, the Shawnee leader Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa (also known as the Prophet) moved their followers from Ohio to the junction of the Wabash and Tippecanoe rivers. It was at this location in 1808 that the brothers founded Prophetstown.

Tecumseh believed that creating a confederacy of several tribes would halt the advance of the settlers. He also hoped to build on memories of the confederacy that resisted the Americans in the late 18th century. Tenskwatawa preached Indian renewal and cultural purity. He discouraged the use of alcohol and disdained the adoption of the settlers’ ways. Often, people view Tecumseh as the primary leader, but in fact Tecumseh rose to prominence only after Tenskwatawa had been rallying support for some time.

Tecumseh Searches for Support

Tecumseh’s recruiting efforts to him to New York, Canada, Arkansas, Minnesota and perhaps as far south as Florida. He visited tribes and persuaded them to abandon their tribal animosities to fight the larger enemy. He encouraged tribes to come to Prophetstown, to stand their ground and resist. But some other native leaders, such as Little Turtle, were engaged in passive, peaceful resistance.

Tecumseh hoped his Confederation’s large numbers would dissuade European-American settlement. By 1808, warriors from other tribes were congregating at Prophetstown. William Henry Harrison, governor of the Indiana Territory, knew of the increased Native American presence at Prophetstown. Historians tell us that tribes represented were the Potawatomi, Shawnee, Kickapoo, Delaware, Winnebago, Wea, Wyandotte, Ottawa, Chippewa, Menominee, Fox, Sauk, Creek and Miami.

The Battle of Tippecanoe

Harrison respected Tecumseh as a statesman and described him as “the Moses of the family … a bold, active sensible man daring in the extreme and capable of any undertaking.” Concerned by the strengthening Confederation, Harrison, in November 1811 (while Tecumseh was away), moved troops to within a half-mile of Prophetstown.

Harrison respected Tecumseh as a statesman and described him as “the Moses of the family … a bold, active sensible man daring in the extreme and capable of any undertaking.” Concerned by the strengthening Confederation, Harrison, in November 1811 (while Tecumseh was away), moved troops to within a half-mile of Prophetstown.

The Prophet feared an attack, so he initiated a surprise strike on Harrison’s encampment. In the early morning of Nov. 11, Tenskwatawa’s warriors surrounded Harrison’s men. Harrison’s sentry sounded the alarm and the battle began. Both sides suffered heavy losses. It is likely that Tenskwatawa’s men ran out of ammunition, pulled back and escaped to Prophetstown. The residents of Prophetstown fled, and then Harrison’s troops burned Prophetstown.

One of the largest Native American confederations ever in North America was wounded, but Tecumseh continued rallying support for his cause until his death at the Battle of the Thames in 1813.